Keely

I like taking a literary approach to genre works like fantasy, sci fi, and supernatural horror and seeing what comes of it.

I love the idea of a throwback, an author who takes cues from classics and puts a new spin on them. Mieville took rollicking pulp and updated it, Susanna Clarke made fairy tales and the Gothic novel sing for a modern audience--but if you're going to write in the style of a bygone great, take only the best, and leave the dross.

By all means, copy Howard's verve and brooding, but skip the sexist titillation. Copy Lovecraft's cosmic horror, but skip the racist epithets. Dan Simmon's Ilium feels like a 50's sci fi story for all the wrong reasons--it isn't as much a throwback as a relic.

We're given several intertwining stories, all of which feature slight variations on the standard science hero, that idealized version of the author that we all roll our eyes at: the adventurer who is a bit dorky, a bit out of place, more at home studying Shakespeare or Ancient Greece in the safety of a library somewhere, but who has found himself stuck on Mars, or launched into space, or trapped in a dystopian conspiracy (respectively), and now must get through it by his smarts and good character.

As any sci fi reader has come to expect from such stories, the plotting is convenient--instead of being motivated by their own internal desires, the plot is just imposed upon the characters. They are vessels through which we experience a story instead of thinking, feeling creatures with their own desires.

The main plots roughly parallel a number of other classic sci fi texts. Like Riverworld , we have these powerful, advanced beings recreating humans and playing games with them, taking on the role of gods as they rebirth our species on another world. The next plot combines elements of Brave New World, and Dancers at the End of Time , where we follow a man on a dying, post-scarcity Earth as he tries to uncover who's really behind it all.

This latter story also has a more interesting antecedent in Nabokov's Ada --as several characters, images, and relationships are drawn from that work, yet it is not an expansion upon Nabokov's sci fi foray, but a regression of his themes back into titillating pulp. The main character just keeps going on and on about how hot his cousin is, and how he wants to sleep with her--however, since he is rebuffed and mocked at every turn, we have to assume that this is meant to be a satire of that style. Yet, we’re still getting those descriptions, we’re still getting that primary point of view, so I’m not sure Simmons is doing quite enough to differentiate the attempted satire from the object of ridicule. Likewise, it’s so overstated and repetitious that it becomes rather tiring.

The Nabokovian turn is a curious one, as it would seem to promise more depth and thought have gone into this work than the average genre adventure. One character lives in a Nabokov story, the next one has constant discourses on the meaning of Shakespeare's Sonnets and the philosophy of Proust, and the last is constantly remarking on literary interpretations of Homer. Simmons is aiming high, he's deliberately drawing comparison with the literary greats, trying to borrow depth and complexity from them--but it's not enough to simply invoke their names, to place their thoughts into the mouths of this or that character, if you fail to integrate these ideas fully into your structure and prose.

Simmons' languages is disappointing--overly explanatory, nitpicking in that familiar sci fi way, where everything is straightforward and reductive. The inner lives of the characters, their motivations, the finer points of the plot, all are stated outright, then rehashed and restated. The reader is told what to think, how to react, and what it all means, and it all becomes rather overbearing. Much of the bulk of this book (and it is bulky) comes from the fact that the author is not willing to leave anything well enough alone. At one point he mentions Hector’s son’s nickname and what it means twice in as many pages--at which point it started to feel like no one actually bothered to edit this thing in the first place.

A grand and strange idea needs grand and strange prose to propel it, trying to narrow it down and simplify it for the crowd just isn't going to do it justice. If you’ve decided to write an odd and complex book, with various story threads drawing on both classic sci fi and great literature, at a certain point you’re going to have to have faith that it will come together, in the end. Otherwise, the anxious urge to control every aspect and get it just right is going to strangle the life out of the thing, overproducing it until there is no room left for mystery or strangeness.

In bad fantasy, it often feels like the author has set themselves the masochistic limitation of constructing a book solely using words and phrases cut from an antiques catalogue--which would explain why, by the end, the swords, chairs, and cloaks have far more developed personalities than the romantic leads. Likewise, in bad sci fi, it feels like the authors were forced to do the same thing with an issue of Popular Mechanics--filling out the text with neat little gadgets and a blurb on the latest half-baked FTL propulsion theory.

We can go back as far as Wells and Verne and see the split between social sci fi and gadget sci fi: Wells realized that it was enough to simply have the time machine or airplane to explore as story devices, as things that might change society, and people. Sometimes, he would go on his preachy tangents, but they were always about the effects of technology, not particulars dredged from an engine repair manual.

Verne, on the other hand, liked to put in the numbers, to speculate and theorize about the specifics of the technology--and yet here we are, still waiting for the development of the kind of battery banks he describes as powering the Nautilus. Going into these intense particulars simply isn't necessary, not in a work of fiction.

A communicator or phaser or transporter is just as inspiring and fascinating on Star Trek without bothering with vague pseudoscience for how the thing is supposed to work. In the end, focus on the story itself, on the characters and the world, and leave out the chaff. The Nautilus is no more (or less!) interesting for a few paragraphs about its engine room, so as in all editing, if nothing would be lost by the omission, best to cut it.

It’s odd to still be getting this in the post-speculative age, where Dick, Ellison, and Gibson have already paved the way for the odd, literary, sci fi story--and whose works ended up being far more predictive of the future than any collection of number-crunching gadget-loving writers. Gibson didn’t even own a computer at the time he wrote Neuromancer , and certainly didn’t go into great detail about the technical aspect of ‘decks’ or ‘cyberspace’, but that didn’t prevent him from being remarkably prescient about how those technologies would change our world. It just seems so odd that now, thirty and forty years after the Speculative Fiction revolution, we should end up praising a regression like this.

Bizarre how much a modern sci fi novel ends up feeling like Tom Swift, with the character constantly mentioning his ‘shotgun-microphone baton’, ‘levitation harness’, and ‘QT medallion’--going into long theoretical digressions about how precisely his ‘morphing bracelet’ might possibly work, on the quantum level, allowing him to look like any person he has scanned--as if we care. And then, of course, he just gives up on it and says he doesn't understand it, after all--so then, what is the point of the digression?

You know you’re reading bad sci fi when the author takes a basic concept that we already understand and have a term for--like teleportation--and then invents his own, new term (or better yet, phrase) to describe the same thing. Sci fi authors can’t seem to get enough of that sort of pointless convolution, an extra layer of complexity that doesn’t actually add anything to the story.

Or they’ll have some other technology, and every time they mention a character using it, they feel the need to describe and explain it all over again. Sci fi is about tech, so of course you want that in there, but once a piece of technology has been established in a scene, you don’t need to reintroduce it every time--we’ll take for granted that the dude still has it and that it works in the same way.

If you want to write a book about robots reading Proust, that’s fine--but don’t then turn around and treat the audience like a bunch of mouth breathing idiots who need to be reminded what X gadget does even though it’s the fifth time we’ve seen it.

Beyond that, the technology in the world makes no sense--they have advanced in huge steps in things like teleportation and energy conversion, and seem to be able to create whole new people and races from thin air, and yet their ability to heal injuries is extremely limited, slow, and cumbrous. It makes it difficult to believe that this book was published as recently as 2003.

Then came that fateful phrase upon which so many a sci fi and fantasy review has turned:

And then there's the depiction of sexuality. It feels quite adolescent--physical instead of emotional, women described at length and men not at all--and not just in the Ada section, where it makes a certain sense as an homage, but throughout the book.

Strip it down to the bare facts of the description, and it becomes the sort of erotica Beavis and Butthead would come up with:

Beavis: So this chick is like, in the bath, and she’s totally of touching her boobs.

Butthead: Yeah, and she’s super hot. And then she stands up, and she’s naked.

Beavis: Whoa, that’s cool!

Butthead: And then she puts on a robe, but you can totally see through it.

Beavis: Heh heh, that’s good, Butthead. And then, she like, rubs her boobs on a pole.

Butthead: Huhuhuh, and then she rubs her thigh on the pole.

Beavis: Like, her inner thigh …

Butthead: Yeah. And then she goes over to this dude, and she takes off the robe, and she’s, like, totally naked!

Is this list of body parts supposed to be arousing? If you were an alien learning the ways of human culture through sci fi novels--firstly, I’m sorry--and secondly, you could be forgiven for assuming that a 'woman' was like any other human being, except that all her limbs had been replaced by breasts, and all her locomotion was achieved by squishing them together and pressing them against things. Is this what passes for seduction? Just 'here’s my naked body, have a go'?

A few chapters later, the same characters are forced to undress together (because 'reasons'), and so we get this long, loving description of what the ladies look like, what the young man is thinking while looking at them, how naughty and exciting it is--and yet, despite the omniscient third-person narrator, no description of the men undressing, nothing about what the women might be thinking, what their point of view might be. One of these women is probably the closest we have in this book to a strong female character, and yet we only experience her through the eyes of a chubby, ignorant dude who keeps trying to sleep with her.

Later on, we get a scene that is ostensibly about her desire, about someone she desires to sleep with--and yet, once again, the whole thing is painted in terms of what she looks like, of her body, of how a desirous man might see her--even though we’re not actually invited into his head to hear his thoughts, how he feels about her. It’s such a blatant contradiction of point of view: the focus on female physical attractiveness is so pervasive that female characters cannot have sexual thoughts or desires unless they are presented in terms of what their own physical beauty looks like.

Since we don’t end up getting an insight into his desires, and neither are we allowed to understand her attraction, or what draws her to him, and yet the description keeps turning back to her breasts and skin and hair, the consummation ends up feeling less like carnal fulfillment and more like smacking two dolls together--except the child has only bothered to undress Barbie.

Then we get to the scene that convinced me to give up on this book entirely.

So, our mooky, bookish hero has been led around by the nose for a few hundred pages, thrown into the plot without any choice in the matter and maneuvered from one scene to the next--until finally, he starts to see that unless he changes his current course, it’s not going to end well for him. At last, he starts to exercise some free will, to play the role of active agent in this book instead of just a passive observer. So, what’s the first thing he decides to do? That’s right, rape a woman. That’s the first decision he makes, the first thing he does that he wasn’t directly made to do by some greater power.

But hey, at least it’s not a violent rape--no, he’s too mild-mannered for that. Instead, he just uses his super science gizmo to make himself look like her husband and then orders her into bed--though he’s so nervous he can barely get the words out, because he’s one of those shy, bashful rapists--you know the type.

He also talks about how many times over the years he spent hanging out in disguise outside her window, just watching her and thinking about her--and then makes a joke about ‘the boobs that launched a thousand ships’, because there’s no better time for humor than when you’re about to sexually violate a stranger. Of course, he remonstrates himself for being a ‘jerk’ for thinking something so inappropriate and crass, because he’s so mild-mannered and sweet--though this momentary self-awareness in no way slows down his rape plans.

And it’s not like up to this point, he’s been some intriguing, fraught, conflicted character who the author has built up to be morally questionable, someone the reader has to think about and whose actions we must come to terms with. No, so far he has been the most generic reader stand-in, a pure observer of the action (that’s literally the character’s job), just a standard nerdy sci fi protagonist who barely has a personality.

To switch immediately from such a flat character to such a fraught moral situation just doesn’t work. I’m not saying authors shouldn’t explore sexual assault, or the type of person who commits it, but in order to actually deal with that idea, you have to first build up the characters to the point where they have sufficient depth to actually delve into that theme in a meaningful way. Otherwise, why include it at all?

There’s no reason I can see that this scene couldn’t have just been a normal sexual encounter. The assault doesn’t add anything to the book, and as soon as it’s over, the author seems happy to just whitewash it and ignore it. Indeed, the victim realizes what’s happening and doesn’t care in the least, then immediately starts questioning her rapist about other things--and after that, happily has sex with him a couple more times.

Is this supposed to excuse it, somehow? Like, if a guy fires off a gun into a house that he suspects is full of children, and then we later find out that it was empty, is that supposed to make him somehow less reprehensible? 'Oh, no one got hurt, so everything's okay--move along.'

If it doesn’t provide new understanding of the main character (or of the victim), and the author is happy to ignore the fact that it happened at all, and just move on with the plot, then what was the point? Why include it at all? Perhaps it’s just exploitation, just pure titillation--which is a hallmark of cheap, thoughtless sci fi. And yet, here’s an author who spends large sections of chapters having characters discuss Shakespeare’s concept of love, or Proust’s--so clearly, Simmons is attempting to present himself as thoughtful and deliberate.

The problem is, if you don’t actually bother to explore those themes through your characters, their personalities and actions, then it simply doesn’t matter how often you have them lecture the reader on the subject--because all you’ve managed to do is write a book that tells us one thing, but then have the actual character actions contradict what we’ve been told. It’s like having a protagonist who the supporting cast constantly praises for being smart and clever, but then every decision he makes ends up being short-sighted and thoughtless.

Maybe it’s supposed to be some kind of cosmic frat bro slut-shaming logic. In the preceding scene, the victim gives this whole long speech about what a whore she is, how the current conflict is all her fault, and how she’s been sleeping with these different dudes because she just can’t help herself, and then she seems to be trying to seduce her husband's brother. So perhaps we’re supposed to sit here and think ‘well, this is all her fault, and she’s just been whoring around for years, causing all this trouble, so really she’s asking for it’

And yet, as any genre fan knows, that's clearly not the worst you can expect--indeed, while Simmons' portrayal of sexuality is one-sided, it's not deliberately so, like so many writers--he's not lecturing us on the inferiority of women--it's just blandly and thoughtlessly sexist. Beyond that, the reader can see that Simmons is trying very hard to do something here, and between that and the passably interesting turns of the plot, it was almost enough to keep me reading. The concept itself should make a fascinating book--this hyper-tech recreation of the Trojan War on Mars, interconnected with Nabokov's 'Antiterra'.

All Simmons' overt connections with literature are meant to establish a place in the canon--just as his genre has been trying to do for a century--perhaps that's why this book was shortlisted for awards, and has been widely praised, because of its obvious attempt to connect to Great Works. And yet, it makes the same mistake as any bad writing: trying to force through repetition and overstatement instead of doing all the difficult work of integrating those ideas into the book. Simmons just isn't doing enough, it's lip service, and the approach is just too rudimentary, flawed, and old-fashioned.

This isn't a forward-looking book, as sci fi should be, its a weirdly nostalgic attempt to redeem the past of sci fi, despite how goofy, exclusionary, and horribly Gernsbackian it was. Certainly, we should take lessons from the past, but good sci fi is always searching out the new thought or experience, exploring what it is to be human, and what it might be like in the future--the scree of gadgets are just a distraction, the same urge some shallow folk have to get the newest iphone, the day it comes out. That isn't a mind seeking the future, it's one trapped in the ever-consumptive obsession over the present, the self, the now.

And I get it, because running on that treadmill feels like moving (especially when you buy a new, cooler treadmill every year) but all that lurching and twitching and shivering is nothing but an ague, and it'll drain you in the end.

1

1

I came to a strange realization while reading this book: that practically every instance I can think of where an author used an unreliable narrator, it's always the same character: he's an intelligent, introspective guy with a slight cynical mean streak, a man with a fairly high opinion of himself (which is constantly reaffirmed by the world around him)--he succeeds without trying too hard, usually in a number of fields, though the success never lasts (because where would the plot go if it did?), he gets into fights and scraps due to his pride, and always wins out in the end--and of course his life is full of a succession of lovely women who flit in and out, flirting, desiring him, ultimately discarded.

It's such an overt, laughably transparent fantasy of the life of a writer that it's simply not possible to take it seriously--which means of course that no serious author would condescend to write something so blatantly adolescent. But, if you take that concept as the base of the story, and then place a veneer of deniability over it, then you can suddenly claim complexity and depth without actually having to write a more unique and intriguing protagonist--you can have your cake, and eat it too.

And yet, I don't quite buy it--it's too convenient to simply say that anything in the book that is stupid or insulting should be taken as sarcasm, while all the good parts were on purpose. It can in a book like Flashman , where the character is so obviously execrable, and the story so obviously a farce--but the more subtle it becomes, the more it is mixed with realism and genuine sympathy, the more character thoughts and motivations become vague, the less pointed it is.

Just as with satire, in order to capture the unreliable narrator properly, you have to do the hard work of separating the subject from the object it is mocking or commenting on, otherwise, all you have done is recreated the object, nearly whole--creating a supposed satire that is hardly distinguishable from the original. Just because an author did something on purpose is not an excuse--they still have to do it well.

And it's not just the main character, Van, who feels like an escapist ideal of the intelligentsia, it's the whole structure--one that should be recognizeable to any fan of Wes Anderson movies. It's all so aspirational--but carefully calibrated so as not to trigger simple jealousy from the moderately sophisticated reader, who feels insulted at being openly pandered to, but will take all the slightly-obscured pandering he can get.

So, we have the wealthy family of good blood--but of course, they've fallen on hard times, they're a bit out of favor, a bit worn down. Money is never really a problem, but neither is their wealth outrageous. The children are all brilliant and charming, well-dressed and good-looking, knowledgeable and full of clever banter. They're good at everything, but they never really pursue any of it (like good idle aristos), and so just have the occasional success, here or there--the sort of thing the average literary person would kill for: a successfully published book, an appointment to a major academic post--but these are always downplayed by the characters as not really important to them, not really as great as you'd imagine. They have oodles of free time to waste in little projects, or bits of melodrama--can't be rushed, darling.

All these pretty people who are just fucked up enough to avoid being totally perfect--though even their flaws are desirable, the sorts of things romanticized in Victorian poetry: they don’t fit in, they are biting and cruel, they are careless, they take too many risks, they're prideful--any ostensibly negative trait that falls neatly under the auspices of being ‘cool’, and doesn't really end up being problematic. It's just so fucking precious I can hardly stand it.

The whole section about Van's supposedly transformative theory of time was just so dull and long-winded. Some authors are able to present a fascinating philosophical or scientific digression in their works, but the long pages outlining Van’s thoughts didn’t feel profound or intriguing, they didn’t confront assumptions, they just seemed vague and half-cooked. The whole final section, about how great the book is and how Van’s thoughts on time changed everything felt overly contrived. Clearly, this is Nabokov, so we’re supposed to assume that it’s ironic and tongue-in-cheek, but I simply don't see how that reading makes it any more interesting.

The fantastical elements were a fun twist, but used too sparingly--they weren’t pervasive as in a work of Borges, or Gogol, or Conrad and Ford’s mostly forgotten The Inheritors . I find such experiments are most effective when they are allowed to change the very texture of the book, to rush through it and alter its meaning and interpretation, as in Harrison’s Viriconium . Here, they ended up feeling too much like interludes, not really integrating with the downright quotidian everyday of the very light plot.

The plot really doesn’t move, aside from a few more frantic chapters, such as the picaresque series of failed duels a la Dumas père--indeed, even the inner lives of the character remain mostly static, so that they are the same people at the end, in their nineties, as they were in the beginning, in their young teens. Of course, this is all meant to relate to the ‘illusion of time’ as Van explores it, but since the theory itself isn't particularly interesting, it does do much to improve the experience of watching a few unchanging people pass through rather everyday events. Indeed, they don’t even same to be creating the sort of false melodrama that we all make of our lives, making coherent stories out of unconnected events and coincidences.

The unreliable narrator shtick also means that we we don’t really get Ada’s side of the romance. We’re constantly being given all the little things Van finds attractive, what excites him about her, physically, but we don’t get to see any of her attraction, how it progresses, what she sees in him, what excites her. It all becomes rather blandly male-gaze, where the charms of the woman are described over and over, yet the man’s physical presence is largely ignored. I mean, we do get Ada's voice peeking through, here and there in notes, but it's never quite enough to tear through Van's veil and let the reader inside the deeper story. Plus there’s the fact that Nabokov had already tackled that dynamic with greater ironic force in Lolita, so it’s rather unfortunate that a supposedly transgressive author like Nabokov would just end up revisiting the same territory over again.

Then there's the prose itself--the first thirty pages are famously overstylized--with the wit jangling and clanking along so conspicuously that it doesn’t leave much room for subtlety or naturalism, for genuine emotion and connection. It’s all such an obviously indulgent performance, like that of a precocious child who must be interrupted: ‘Yes yes, you’re very clever--now was there something you wanted to tell me?’.

After the initial bombast, it settles down and the style almost completely changes for the rest of the book. The change is jarring, and didn't seem to have any purpose, or reason behind it--though it's not as if Nabokov lays off the wordplay at that point, it just settles out a bit. Indeed, it started to make me tired of puns--which is odd, since I’ve been a longtime proponent. It began to feel like too much work for too little payoff, that puns simple work better in conversation than in books, because a book is so carefully crafted, one can afford to take one's time and perfect it, polish it up--while a rough pun's strength is in its suddenness, its extemporaneous quality. But then. with Nabokov, the sheer amount of work seems to be the point, that all the glitter and movement on the surface is worth all the trouble it takes, that we’re not meant to appreciate the joke itself, or the punchline, but all the circuitous labor the author went to to set it up in the first place.

I began to feel a funny parallel between Nabokov’s style and the chapter about the fellow who cheats at cards with mirrors, surrounding himself with all of these ostentatious, flashy bits that he’s constantly tweaking and nudging to get them to work--and we’re supposed to think of him as pitiful, watching as he’s easily dispatched by the ‘true’ sharpery of Van, who instead manipulates the cards without it ever being obvious, due to his sheer master (well, until he’s unable to hold it in and flashes one from his sleeve at the end)--yet one begins to think that if Nabokov were at the table, he wouldn't be able to resist flashing his sleeve every hand, and thereby ruining the effect from the outset.

And such a style can work for a farce, because it is so overblown, and the characters and plot aren't really central, but often act as set pieces for absurd situations and wry commentary on the nature of life. It can also be effective in works like Sartor Resartus , or Moby Dick , or Gormenghast , where the language is inextricable from the characters, where an almost overbearing style is used as a tool to delve deeply into their thoughts, their point of view, to force the reader into the thoughts and senses of a person that is completely different, a world with colors and textures and relationships that pierce through its very fabric, through the land itself, the characters' flesh and hearts and minds, then drag the reader back through that hole like a baited hook.

But Nabokov's voice is not pervasive enough, it spends its time flitting along the surface, and so fails to enmesh wholly with his world and characters. It begins to feel more like a compulsion for wordplay than a deliberate construction--a love of words just spilling out onto the page because Nabokov is fascinated with language. The fact that the book spends a chunk of time discussing how to play Scrabble should tell you all you need to know. After all, he was a man who grew up a multilinguist, suspended between various languages and dialects and forms of communication--who wrote the English version of Lolita himself.

Of course, it should be noted that my own skills in languages outside of English are fairly pathetic--my years of Italian and Latin were some time ago, and so I unquestionably missed innumerable little asides and jokes. Yet, the jokes I did get, even the more obscure ones, like a veiled reference to an old name for Tasmania which I only got because I happened to reference in my book, weren't especially amusing to begin with--and so it simply didn't seem worth the time to go through and decode the rest of it--just another case of more time spent for insufficient reward.

And yet conceptually, it has its strengths--it is an interesting and unusual book, clearly a case of an author throwing himself into a wild experiment, which certainly takes courage, and if he didn't always succeed, at least he was always moving, always probing and doing something. It wasn't an insulting work, it wasn't simplistic or flat, and that was what kept me reading through to the end, that even if I don't think all the pieces quite came together to make it work, it was something curious, something worth experiencing and rolling around in my mind.

1

1

As a writer, it's hard for me to imagine how people can just keep writing the same thing, over and over--just providing slight variations on the same plot, characters, and setting, where the only thing that changes are the names. At that point, it's less a creative endeavor than the symptom of a neurosis: an obsessive need to recreate the same familiar pattern, over and over, in hopes that it will free you--and truthfully, I can think of few better ways to murder creativity than to write in this way.

Of course, we writers have certain interests and concerns that are going to crop up again and again, our favored themes, whether it's PKD's paranoid uncertainty of self or Le Guin's mutual cultural incomprehensibility, but as long as we keep finding different angles of approach, different ways to explore these themes, then we're not just treading water.

Of course, I know that many writers do it to get paid, and that in any field, after years of working your way up with fresh ideas and hard work, it can be tempting to sit on your laurels and stop really trying, just letting the paycheques come in--hell, plenty of folks end up at that point without ever having had a fresh idea in their lives. I mean, I've written ten thousand words in a day before, so if I wanted to pump out a generic fantasy novel every week, I'm certainly physically capable of doing so--it's the mental aspect that prevents me.

Not just the fact that I can't stand the idea of filling the world with more generic crap (which I can't), but the need to completely turn off my brain and not care at all about what I've made--and that's part of what makes Moorcock interesting, is that he is clearly capable of not being critical of himself. He has a reputation in the field of being able to turn out a short story faster than anyone else, and I have sometimes gotten the impression from various works of his that his pen was outstripping his thoughts--because he has produced works like Corum, which is more or less a rewrite of Elric with slightly duller characters and slightly weirder cosmology--but then he comes along and writes something like Gloriana, or An Alien Heat.

It's as if you took a writer as flat (though intriguingly madcap) as E.R. Burroughs and told me that he'd tried his hand at something in the style of Conrad and Ford's The Inheritors--it's such a complete change in voice and approach. Indeed, Moorcock's book has much in common with that tale of profound intelligences lost in the stream of time, the past and future colonizing and changing one another in unpredictable, unexpected ways.

As with Gloriana, Moorcock is working in a completely different voice here, a different tone and pacing. While in Corum, the romance may be central, it is perfunctory, accomplished in a moment, without bothering to delve introspectively to shore up its foundations--no real depth of feeling is ever produced. Yet here, the romance is the plot, is the conflict, drawn out over the length of the series, the back and forth of it, the inner turmoil of it all are more Darcy of Pemberly than Carter of Mars.

Instead of revolving around a series of cosmic villains, as in Elric, it is a story built upon the decisions and feelings of its characters, built from the inside out instead of imposing some artificial external conflict upon the characters to motivate them--and the former method is always going to seem more personal, more vital, and more perilous to the reader, even when the stakes of the conflict are much lower.

Indeed, in terms of sci fi tropes with farce, Moorcock seems to be laying out a prototype for one of my favorite series: The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Indeed, in the third book, when Moorcock's characters are trapped in the beginning of Earth's history, the parallels are almost too remarkable to be coincidence.

However, Moorcock does not quite have the precision necessary for a well-turned farce, as Wodehouse so often demonstrated, where the timing and rhythm of the scenes must be constructed with great care in order for them to work like the well-oiled machines they are. As such, in his pointed satire Adams ends up perfecting the form that Moorcock laid out--as is so often the case with his grand and intriguing but somewhat rough ideas.

However, An Alien Heat does share some shortcomings with works like Corum--quite literally, in that the exceedingly strange and imaginative world that he sets up for us is populated with characters who are all too mundane. In a world that is not only post-scarcity, but in which people have an ability to reshape the world to their liking beyond the wildest dreams of virtual reality, it seems odd that the characters would stick so closely to modern conceptions of identity.

For example, if a person can change their gender at will, or negate it entirely, or invent a new one, you aren't going to see the same old gender roles continue on as if nothing has changed. In a world where physical identity and appearance are completely fluid, you would expect peoples views of themselves to be similarly mutable.

Likewise, in a world where people can create anything with a thought, things like gold and gems would no longer retain the status rarity affords them currently--indeed, Moorcock often touches upon the fact that really, the only thing that produces value in his world is novelty, and yet he does not always succeed in demonstrating this effectively in his actual descriptions.

There are certainly good touches--that once we have all we want, things like depression or moroseness become interesting as poses, as markers of difference for their own sake, even when they aren't necessary--precisely because they aren't--but he might have done much more.

Indeed, one can also see the effect the work has had on another great writer who took the ideas and ran with them: Moorcock's protege M. John Harrison, who in his Viriconium series does begin to explore what a world of such profound difference might look like, where things like reality and identity begin to lose their meaning, and cohesion in the face of an ever-shifting world in which very little can be taken for granted. Once again, in the third book, when Moorcock gives us his hallucinatory cities, intelligent entities dying and going mad out in the wilderness, where most folks are happy to leave them alone, though some are drawn in by curiosity, we see a blueprint for the world that Harrison will later present us.

I do think that this book ends a chapter too late--that the conclusion Moorcock gives us originally produces an intriguing tale along the lines of Kafka, almost an inversion of Bierce's classic Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge. As it is, Moorcock gives us a denouement which is altogether too tidy and easy, wrapping everything up and explaining it away, which I think would have made a much better opening to the next book.

Then again, perhaps his mainstream sci fi publishers were not ready for that sort of book--just as they weren't ready for Harrison, and put a Burroughs cover on his Kafka story. In any case, while the next book in the series is a bit of a lull, giving us much of the same, over again, the third book does much more with the setting and characters--even if the conclusion is a bit tacked-on.

Overall, the vision Moorcock gives us here is a testament to his creativity--he does not stick to just one story, or just one kind of world, even when his worlds are all interconnected, he still manages to give each one its own tone and voice, and second only to his masterwork, Gloriana, the End of Time series is one of his most intriguing.

2

2

Moorcock has a reputation among fantasy editors for the speed with which he can turn out a story--call him and tell him you have a slot in an upcoming anthology that need filling, and he'll send you something the next day. It reminds me of an old truism in writing: if you never seem to be able to finish anything, then you're too critical of yourself, but if you are finishing things constantly, then you probably aren't critical enough.

That isn't to suggest that Moorcock has a swell head--from everything I've heard, he's a pleasant, self-effacing fellow--but that perhaps sometimes, his pen ends up working faster than his brain. I'd heard that the ideas he begins to touch upon in early works like Elric don't start coming into their own until later pieces, like Corum or Von Bek--which was why I was surprised that a number of elements in Corum felt less sophisticated than their treatment in Elric.

Unlike Elric, Corum doesn’t maintain his internal conflict throughout. Though he comes from an artistic, intellectual, peaceful background originally, this doesn’t really color his later actions or thoughts. Once the ‘badass warrior switch’ is flipped, that seems to be it, and he’s onto his new life. Certainly, there is a sense that he wants this to be over with, so he can return to a state of peace, but one would expect that his former life would change the way he approaches being a sword-weilding demon fighter, but it simply doesn’t seem to.

Doubtless, there was plenty of reason for the character to change--his whole life, everything he knew was ripped away from him--but I still would have liked to see that transformation play out, to see the contradiction between how his expectations and assumptions just don’t match the world around him, and the life he is forced into living. The whole story of his race is that they are ancient, wise, but naive and out of touch, and it would have worked better to see more of that in Corum, instead of the ‘take it as it comes’ style of the average sword and sorcery hero.

Likewise, the romance, while a central part of the story, is dealt with in a rather perfunctory fashion. We don't really see how the characters fell in love, or why this particular relationship formed, and so it ends up feeling less personal and more like a plot point--especially when compared to something like Dancers at the End of Time--but then, that was an occasion where Moorcock really took the time to get into the characters heads, to let the romance develop over the course of several books, and to explore the conflicting feelings at its heart.

Of course, it's not quite a fair comparison to make, since in that series, the romance really is the central plot, while here, as important as it might be to Corum's character, it's still secondary to the massive multi-dimensional conflict that takes center stage. It's unfortunate, because by focusing on that, he really could have separated Corum from Elric, who hardly has much time for sentiment.

The introduction of the dimension-hopping heroes' companion in book two didn't work especially well, either--like in Leiber's Swords of Lankhmar , the series suddenly takes an odd left turn, introducing this silly dimensional traveller who suddenly starts explaining the makeup of the universe and other such dull exposition.

We were reading a story about a man embroiled in a great conflict, but also a personal one--trying to avenge the death of his family, the only life he’d ever known, who has since become bitter and broken through struggle, but who has also found love, and keeps fighting for the sake of that love. To have this secondary character burst in with a completely different voice and tone, insisting that Corum is just one of many distracts from his story, cheapens his struggle, and makes the whole thing feel oddly goofy, especially compared to the opening book.

From there on, especially as we go into the third book and near the climax proper, the story becomes more piecemeal, where each scene begins to feel more like a self-enclosed event. It’s very much the cliche pulp approach, where this happens, then this happens, and we’re technically moving forward toward the final conflict, but the individual episodes aren’t placed in a meaningful order. It brings to mind the old writing adage that every scene should be followed by a ‘but’ or ‘therefore’ which connects it directly to the next scene. It’s not enough that they’re simply given to us in a certain order, they must be reliant on each other, there must be a sense of build, of inevitability, of meaningful connection from moment to moment.

The writing likewise vacillates in quality, from the flat exposition of the prologue to the quite visceral and imaginative scenes in the palace of the horrid chaos god Arioch at the end of book one--which indeed, are much more effective than the climaxes of the next two books, making them feel rather underwhelming in comparison.

But for all that, I can see why people find Corum to be an expansion on Elric, because there is one very real way that Moorcock is pushing the envelope here: the shifting dimensions, the alternate realities and identities, and layers of contradictory worlds are a great way to push the boundaries of what fantasy is, and how it operates--and yet, I'm reluctant to give Moorcock his due here as the self-defined 'bad writer with big ideas', because these aren't quite ideas.

What he's doing here is playing with form and structure, with the symbols that authors use to explore their ideas--but he's not creating themes and concepts beneath these symbols to hold them up and give them meaning. Magic is a symbol, and there are many different ways magic can be presented, and many ideas we can explore through our magic. However, far too many authors are content to simply produce complex magic systems without ever bothering to connect them to meaningful themes and ideas.

As other authors have proven in later books, like Viriconium and Bas-Lag--or even games like Planescape-Moorcock's symbolic innovation provides an exceedingly rich field of play for any writer to explore and represent a plurality of ideas--but unfortunately, Moorcock himself does not do much with them here.

Likewise, his focus on law vs. chaos instead of good vs. evil presents a number of interesting opportunities, from entropy and the Social Contract to the nature of the creative spirit, itself--but again, he's not pushing these representations very far.

It's the same problem he has in Dancers at the End of Time: he's given us a very strange and complex world, but the characters and themes in the book just aren't strange enough to match it. The structure Moorcock presents, wherein different individuals from various times and dimensions might come together, and that some of those individuals are really the same person, expressed in a different age--that’s quite interesting, but it’s also disappointing that he doesn’t do more with it. What does it mean for one person to meet a different version of himself? How does that feel, how does it affect him, moving forward? It should certainly offer some profound insights, or at least force us to confront some common preconceptions.

Likewise, it’s a great opportunity to explore the nature of storytelling, itself--the fact that we authors do keep writing about these similar kinds of figures, who really do feel like ‘versions’ of the same hero, or love interest, or villain--one begins to imagine the way that Gaiman would approach it. Once again, it’s something that Harrison spends a great deal of time exploring in Viriconium, where the same plot and characters are destined to recur, over and over again, but with such different pacing, voice, and tone that it becomes clear that these standard forms and types are really not the heart of the story--that indeed, they become almost superfluous.

After all, think of all the various stories in any medium, books, movies, comics, that play out pretty much exactly the same, whether they take on the form of the monomyth or the murder mystery or any other, with the same standard character types (hero, sidekick, wise man, love interest, villain, henchmen)--and then realize that this has nothing to do with the quality of the work. It’s all the other stuff that makes it good, that makes it feel original--or fails to.

The fact that, to combine their powers together, the characters are compelled to link arms and form a sort of cosmic kickline certainly does not help to make the experience feel as profound and strange as meeting an amoral albino version of yourself ought to--and really, what else is a good fantasy book but an opportunity to meet a version of yourself you'd never previously imagined could exist?

In the end, Moorcock gives us a blueprint for what the curious future of fantasy might look light, but sadly, it's largely inspirational because it invites other writers to fill in the holes he's left in his story, to take that huge, complex symbolic structure and really make it do some of the heavy lifting--and happily, they best fantasists of the modern era have done precisely that--but it's still a bit disappointing that Moorcock himself didn't sit down and take the time to give us his version of it.

1

1

George MacDonald's 'The Wise Woman and Others'

The title story of this collection is exactly what you would expect of a fairy tale written by a minister and subtitled 'a parable', which is to say it's not particularly fantastical, and feels a great deal like reading a sermon. Condescending and blandly didactic--MacDonald never lets an image or symbol stand on its own, but must always hem and haw about it, telling us what is right and what is not.

There is little enough wonder in it--we are told what to think and why. the focus is always on little errors and rules and flaws of character, never upon anything grander, nothing to ignite man’s imagination or awe--indeed, it is all terribly petty.

He seems to think of children as awful little monsters, naturally disposed to self-destruction--and the only way to fix them is to put them through a series of strange tortures. They are not corrected and taught by example, or by interaction, or explanation, or by forming any kind of genuine relationship with the child, but rather by leaving them alone and letting them grow more and more confused, miserable, and terrified. At one point the 'wise woman' uses her magic to make a child think she has accidentally killed her playmate.

Of course, anyone familiar with the tradition of English Boarding schools, whether through 'school stories' or the autobiographical accounts of figures like Roald Dahl, C.S. Lewis, and George Orwell will recognize this sort of distant, abusive ‘hard love’ that English schooling became infamous for.

His view of humanity just comes off as so negative--so prejudiced and judgmental--and at the same time condescending. The Wise Woman of the story is entirely convinced that hers is the proper way, that no matter what she puts the children through, abandoning, confusing, and demanding things of them, it is the right thing, and will prove so in the end. Of course, in fantasy the author can create whatever sort of world they want, one which reflects his own whims and judgments, and which in the end justifies them, producing whatever effect is required.

That is why didactic works like this are so far inferior to open-ended works like Dunsany’s, which show us remarkable things, lead us through strange, new thoughts, instead of insisting that we take from it any particular message or lesson.

Dunsany is not top-down, he does not require that you believe as he does--he is not so conceited. Instead, he intends to open the world to you--not to tell you something which he thinks you ought to know, but to share an experience with you, not doling out from on high, but engaging in a give-and-take--an opportunity for both author and reader to learn and grow and see the world anew.

All in all, it is not surprising to learn that MacDonald mentored C.S. Lewis, as there is that same sense of being alternately scolded and coddled by a pretentious schoolmaster. However, the last few stories which make up this collection, while much briefer, do not suffer from this same voice. They are a bit plain, but they are not judgmental or sermonizing--indeed, there are some clever and humorous bits of dialogue in them.

It gives me hope that perhaps some of MacDonald's other stories are more pleasant and wondrous, and that I've just chanced to stumble upon him at his worst--I've certainly heard promising things about works like Phantastes and The Princess and the Goblin, but I fear it will be some time before this foul taste disperses and I feel up to cracking open another of his books.

2

2

M. john Harrison's 'The Pastel City'

Fantasy has always had its moralizers and its mischief-makers, those who use the symbolism of magic to create instructive fables, and those who use the strangeness of magic to tap into the more remote corners of the soul, and then obscure their transgressions behind the fantastical facade. Like Moorcock, Leiber, and Vance, Harrison is playful, he is rebellious.

Indeed, in his swift, pulpy approach, Harrison very much resembles those authors, but his voice sets him apart. There is a scintillation, a sophistication, a turn of phrase which shows a practiced hand, and unlike many fantasy authors, Harrison's voice is very consistent. He is aware of what he is doing, the effect he means to produce, and he generally succeeds.

Moorcock was fond of saying that he was a 'bad writer with big ideas', and the same can be said of many genre writers, from R.E. Howard on, but Harrison is not a bad writer, and it's enjoyable to see someone of his skill take up the torch--leaving no doubt why he was so successful in inspiring New Weird authors like Mieville and VanderMeer to tear into genre (with varying degrees of success).

He had already made a name for himself as an editor and ruthless critic working at Moorcock's New Worlds, often lamenting the shallow predictability of genre fiction (his critical work has been collected in Parietal Games ), and this is clearly a stab at trying to break out of that monotony--to practice what he had been preaching. It is rather less wild and experimental than his later works, but there is something very effective in the straightforward simplicity displayed here.

The most obviously groundbreaking aspect of the work is his setting (not, as Harrison would insist, his 'world'). He combines science fiction and fantasy tropes quite freely, but with much greater success than Leiber's clunky attempts, and much more overtly than Moorcock's nods to quantum physics in Elric. It acts as a reminder that despite all the purists trying to drive a definitive wedge between the genres, they are really doing the same thing: creating physical symbols through which to explore ideas (it's Clarke's Third Law again).

An easy example is Star Wars, a fantasy story about wizards, prophecy, spells, magic swords, funny animals, good vs. evil, and the monomyth which adopts science fiction only as an aesthetic, a 'look'. It isn't forward-looking, it's mythical, which is why the laser beams only shoot at a fixed point in front of the ship, like World War I biplanes. Nowadays, the concept of mixing fantasy and sci fi has trickled down into the public consciousness, showing up in cartoons like Adventure Time--and to a large part, we have Harrison to thank for that, because his version (complete with laser swords) came years before Star Wars, and also presents a much more nuanced view of the world.

On the surface, Harrison's rusted-out future world resembles Vance's, but it's much closer to fellow New Wave Britisher J.G. Ballard (or Le Guin): a fantastical headspace of extremes, when everything is dying and collapsing around you, and yet life goes on--dwindling, certainly, but fundamentally not very different from how it has always been. It’s a portrait of existential dread, our fear of being alone, our foolish habit of nostalgia, of seeing the past not as it was, but as a sort of promised land, a missed opportunity for our neurotic brain to cling to.

The dying world is the legacy of poets (at least, of the Victorians, who have the most influence on our modern notions of the poetic self), from Byron’s Darkness to Shelley’s The Last Man and the mythology of Blake--and of course arch-pilferer Eliot’s The Waste Land. Indeed, in this post-modern world, it’s become almost trite to riff on The Waste Land and it’s world built around the sad, intellectual man who regrets that all meaning has been stripped away, and he’s left to figure it out on his own.

However, fantasy has long been lagging behind, particularly highly-visible epic fantasy, like Tolkien’s, which behaves as if existentialism and skepticism never happened, instead inundating the reader in a top-down, authoritative voice full of message and allegory and obvious symbolism--though Tolkien himself often denied that this was the case, as a believer, to him the real world was a symbolic allegory.

The 'dying Earth' is the same old trick of fantasy, to take a state of mind and literalize it, to produce a setting that reflects it, and through which the author can explore it. It's like how in a Gothic novel, it rains when people are said, and lightning strikes as the villain observes the results of his cruelty.

Sure, it's also what a comics writer does when he puts the fate of the world at stake to increase the tension--but I won't say it's a bad trick, or a dirty one--it all depends on the magician who is using it. Are the a con artist, trying to win us over and sell us something, or are they a trickster like Houdini or James Randi, forcing us to confront the fact that we can so easily be fooled--indeed, that we may want to be fooled.

I find Harrison to be a trickster, an invoker of our better nature, if only because he realizes that the mind can be unsure--it can change--so, what happens to a world founded upon a changing mind? It's a question Harrison only touches on here, before diving in headlong in the next book, and finally getting a grasp on it in the third and fourth.

Unfortunately, one area where Harrison fails to meaningfully improve upon earlier genre outings is the portrayal of women. They are rarely present, and when they are, they tend to the weak and distant. We don't get inside their heads as we do the male characters, and so they do not really feel like complete characters, but objects of focus and motivators for the men around them. I mean, it's not like we're getting a trite Madonna/Whore love triangle, like Tolkien's, but moving from 'bad' to 'neutral' isn't much of an improvement, especially for a book written in the seventies--and the portrayals don't get much deeper in the later books.

I've often complained that many genre authors (like fellow dying-earther Gene Wolfe) give you two hundred pages of plot buried in four hundred pages of explanation, description, exposition, repetition, and redundancy--but I'm glad to say that in Harrison's case, he's happy to give us the two hundred and leave off the rest.

My List of Suggested Readings in Fantasy

1

1

Jeff VanderMeer's 'City of Saints and Madmen'

Sometimes it doesn't matter what you hear about a book, all the promise described in glowing reviews--it doesn't matter who suggests it, on what authority or with what arguments. Sometimes, you're still going to come out the other side disappointed, confused how this could possibly be the book you had heard about, trying to reconcile the words of friends and fellow reviews with what you find on the page.

I'm there again. There's something in it reminiscent of the moment after a car accident, where you're sitting there in disbelief, trying to make sense of it, half laughing, half shaking your head.

It's not that I don't see it--the book certainly has the right markers: the self-awareness, the meta-fictions, the ironies and self-contradictions, the allusions and in-jokes, the big, rearing ugliness of modern literature. And yet to say that it has those markers doesn't mean much--it's like saying that a math book has equations, it doesn't mean that they add up to anything, that they're accurate.

Indeed, markers are the easiest things to fake--we all know what a piece of literature is supposed to look like, and so we can take the right words and the right techniques and include them. But of course, you can use a word without understanding its definition, and you can adopt a technique without ever considering why that technique is used.

The most obvious marker, at first glance, is the self-awareness of the text, what the kids these days call 'meta'--where not only are you writing, you're also commenting on the fact that you're writing, making jokes and references, reminding the reader of the artificiality of what they are reading.

It's a trick at least as old as Ariosto and Cervantes, but which has become especially popular in this Post-Modern Age of Skepticism. After all, we're not supposed to trust authority, we now take it for granted that the book is not the 'Logos', the Word of Truth, and so it makes sense for the author to step out occasionally and acknowledge that. And yet, since it is the default now, it's really not enough simply to be self-aware, just to poke at the fourth wall for the sake of doing it--that's played out.

Much of the self-awareness takes the form of a jokey, silly tone, and much like in Iain Banks, it seems to be an ill fit for otherwise dire and serious stories. More than that, VanderMeer is constantly harping on it without much payoff--there are some truly clever pieces of wit, here or there, but for every one that hits its mark, we have to wade through ten others that don't.

It starts to feel like being at a party with a guy who has to make some comment about everything, who keeps mentioning that people think he's funny, who tells you how funny his jokes are before he tells them, says 'wait for it!' before each punchline, and then explains the joke once it's done. In King Squid he writes:

“... six hundred continuous pages of spurious text that no true squidologist can read today without bleeding profusely from the nose, ear, and mouth.”

And it just feels like a bad internet comment--it's edgy, full of hyperbole, and so non-specific that it could have been appended to pretty much anything. That lack of precision makes humor impossible--because being funny means hitting your target right in the heart, not just pelting some refuse near it. From the same story:

“... the Society ... was unwise to choose as observers the Fatally Unobservant.”

The observers were unobservant. That's not even wordplay, it doesn't even reach to the level of the humble pun--and it's giving me unpleasant flashbacks to Discworld.

In his introduction, Moorcock compares VanderMeer to Peake, but he just lacks any subtlety, and it all smacks of trying too hard, just worrying incessantly at the edges until they all begin to fray. When he mentions the Borges Bookstore (on Albumuth Boulevard, natch), which he does in every story, it's a nudge that threatens to bowl the reader over, a wink by way of facial spasm.

It's not only with his jokes and allusions that VanderMeer leaves nothing to chance, he has characters tell us in footnotes when we are supposed to think they are funny, he mentions when a certain part is deliberately over-written, or that we shouldn't trust some character, or that this point-of-view shift indicates a change in the character's personal identity.

Yet this is a book that people say is challenging, is intellectual and mysterious, something you have to put together yourself, piece by piece. My idea of a challenging book is one that trusts the reader to come to their own conclusions, to figure out the themes for themselves, and to find humor where it lies, not one that leads them along by the hand. Sure, sometimes his instructions are contradictory--we're told at first that something is important, and later that it's not trustworthy--but the real problem is that we're being told outright at all.

A lot of this self-awareness takes the form of self-deprecation, as in this line:

"Throughout the story, X communicates to the reader "between the lines" in a rather pathetic manner. Such self-consciousness has clearly corrupted his writing."

But self-deprecation is only effective when it is honest, when it acts as a genuine reveal of character, not just a sarcastic defense mechanism--a schoolyard dodge, 'if I say it first, then they can't make fun of me for it'.

Self-awareness needs to be more than just a pose, because otherwise, you just fall into teenage rebellion, where it becomes an excuse, a crutch, a way of distancing one's self from the reader, and from judgment--'Yeah, I know--Did you think I didn't know that? Everyone knows that.' It becomes a crutch to fall back on, an attempt to regain some semblance of control, just like all the explanations of what the reader is supposed to be getting out of this.

Certainly, VanderMeer set himself a great task, and there's something admirable in that, but it isn't one of those great, inspirational 'troubled experiments', like Moby Dick or A Storm of Wings--in large part because Harrison manages to achieve in A Storm of Wings everything that VanderMeer can't seem to do here. However, Harrison always lets the story stand on its own, he gives no excuses, nor does he spell out what we're supposed to take away from the book.

It's a lesson all artists need to learn: if you're going to be brave and create something, then be brave all the way through. Don't stop halfway to explain yourself. When you hand off your work for others to enjoy, don't include qualifiers and excuses--even though the urge to do so will be strong. You have to let the work stand on its own, and if you aren't willing to do that, then don't take on a monumental task, because the meddling will ruin it.

And VanderMeer set a monumental task for himself--there are a lot of moving pieces here, and keeping them all spinning is a master's work. The structure itself is obsessed with metafiction, with all of these 'in-world' documents that are supposed to come together and produce a greater whole: a scientific article about squid, a series of art critiques, a pamphlet about the history of the city, an asylum doctor's interview, letters, a story written in secret code, and several more.

Yet, I rarely found that these metafiction elements were well-written enough to merit inclusion--they certainly paled in comparison to the pure fiction stories. Indeed, there seemed to be a sense that they were all extended jokes--in An Early History of Ambergris, the fact that there were more footnotes than actual text, and the same in King Squid, except this time it was the bibliography that was longer than the story, or in The Release of Belacqua , mocking the fact that art critics can often only guess at their subjects' motivations.

But all of these jokes relied on their great length, the need for the author to just keep at them, to keep extending them ever longer, which only actually works if the joke is funny enough in the first place to survive such a stretching on the rack. What marks great lengthy jokes is the author's ability to keep raising the stakes, to keep making things more ridiculous and involved, to drop the other shoe--and then another--until it's all piled on top of itself, redoubling its own absurd premise. Instead of this, VanderMeer keeps the same pace throughout, merely adding on more of the same, and so the last line holds no more humor than the first--indeed, rather less by way of attrition.

The central story that connects all of these it The Strange Case of X, which literalizes the fiction process, writing the author into the story, making him the god who creates the world, but is also trapped by it, by his own obsessive imagination. Again, it's an old trick--I found it trite when Grant Morrison first pulled it out (not to mention the third, fourth, and fifth times), and I still think it's something rather difficult to pull off. It forms a sort of 'answer' to Harrison's conclusion to the series, A Young Man's Journey to Viriconium', but again lacks the necessary subtlety and conviction.

Comparing Sartor Resartus to A Brief History of Ambergris, for example, a great deal of what makes the former so successful is that our crazed academic takes himself so seriously even as he spouts the most absurd nonsense--indeed, we almost feel we believe him. In contrast, VanderMeer's is constantly telling us how funny and silly he is, and as such, he feels less wonderfully absurd and more 'look at me being wacky'.

I got the impression that The Strange Case of X was supposed to be a sort of surprising twist story, forcing us to question our assumptions about the nature of reality versus fantasy. However, right from the beginning, I assumed the twist--I’m not saying I cleverly figured it out, but that it never occurred to me that the story might end any other way. It would be as if a story ended with the revelation ‘he was a dog all along!’, when the first several stories in the collection were also from the point of view of dogs, and the story in question kept mentioning leashes and chew toys. Perhaps if it were read in isolation, it would work better, but when collected with other Ambergris stories, it's hard to imagine reading it any other way.

Then there's the fact that these metafictions tend to fall into worldbuilding cliches, where the author literally sits you down and dumps a huge pile of exposition on the reader, not only explaining the history of the city, but also giving comments along the way suggesting how you should feel about it. It struck me that one of the only times I've seen this done well was in the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy , and that's only because it was clever and witty enough that the worldbuilding didn't matter, it was completely secondary--indeed, if you took any one of those entries completely out of context, it would still be amusing.

Susanna Clarke managed to do the same thing with her footnotes, and it's a lesson all authors should learn: always be putting on a show, so that your words do double duty. Don't just be self-aware, be self-aware and funny, don't just be funny, be funny and thoughtful, don't just be thoughtful, be thoughtful and exciting.

Otherwise, it becomes the equivalent of Gene Wolfe's New Sun books, where there's supposed to be this huge, complex, interesting meta-story behind the real story, as long as you reread it and carefully put together all the pieces--but why would anyone want to reread a dull story over and over in hopes that it might become interesting? It becomes the equivalent of the epic fantasy standby: 'You have to keep reading until the fifth book, that's when it gets good. A good author ensures that the story is intriguing on both the small and large scale.

Also like Wolfe (and Banks again), there are some very cliche problems with character and point-of-view. Just like in bad Steampunk (meaning most of it), where authors completely forget the 'punk' and make all of their characters upper class and educated, VanderMeer doesn't give us any views from oppressed or minority classes. It's all about the difficulty of being a smart, middle-class white male artist (or scientist).

Women are largely absent, except as objects of desire. We don't get to go into their heads, to see their point-of-view, we aren't asked to explore their struggles or concerns. Even as objects of desire, there's never any relationship or intimacy, just distant, creepy obsession. Indeed, the only genuine, long-term romance represented in the book is between two men.

The title character of Dradin, In Love is typical of such, being an obsessive creep who fantasizes about a woman he's never spoken to. Dradin is an ass of a character, but this isn’t the worst crime--many such asses in fiction are amusing, insightful depictions, even as we roll our eyes at their foolishness or cringe at their cruelty, we laugh and even sympathize with figures like Flashman or Steerpike. Dradin’s true sin is that he’s both unpleasant and dull--I don’t mean merely unassuming, like Chekhov or Kafka’s quotidian characters, but flat.

However, there is an implication that this is all on purpose, that he's meant to be this way--but of course, doing it on purpose isn't a justification, just as being 'self-aware' isn't--so, why is he this way, is it a parody of such characters in fantasy? Well, Dradin starts off an obsessive creep, and grows increasingly obsessive and creepy as the story goes on, demonstrating it twice and three times over.

Perhaps it's written for the reader who will, at first, assume that Dradin is a genuinely nice guy, and who will then be shocked and appalled at his later behavior? If so, then all VanderMeer has really done is write a fable for the naive--what does this present for a reader who dislikes him from the start? Not very much, I'm afraid, which is why it's important to make sure that a story works on multiple levels, such that it can interest various audiences at the same time.

There is a point, in any piece of art, when to add a further stroke would worsen it, would make it too busy, would destroy the sense of fluidity and gesture. Every artist knows this point exists, but for most of us, we only recognize it once it has passed, once we have already ruined it, and it becomes abundantly clear that we should have stopped a moment sooner.

Yet, there is a need in us to keep going, to keep carving away at our work--especially when we see the errors in it, which we always do. Once you've passed that point of no return, where each additional mark just muddles it a little bit more, it can be almost impossible to stop, to salvage something from it. Much easier to start over--and usually, to make the same mistake again.

An embarrassment of wealth becomes a wealth of embarrassment so easily when we overreach ourselves, when we are striving for something and all along feeling that it's too far beyond us even to approximate it. VanderMeer's work is full of reaching, and full of self-corrections, of tiny modifications in the course--because he is steering by the bow of his ship, not by the horizon.

Markers are easy to imitate, which is why VanderMeer can write

"On the thrice chime, a clerk ... came forward"

And if you weren't paying attention, if you didn't quite know what to look for, it might seem somehow interesting to mistake an adjective for an adverb--to use an odd word without really understanding the definition. What a shameful, whence the thrice badly book failure the aspiringly author.

2

2

Your Guide to Free EBooks

|

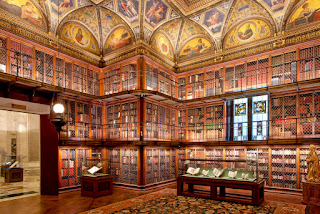

Pierpont-Morgan Library |

The internet is a great resource for readers, and I take advantage of it as often as I can. Copyright Law is a complex animal, but basically, anything published before 1923 is no longer in copyright in America--and many later works never had their copyright renewed. In countries like Canada and Australia, copyright does not extend as far back as it does in America. And whenever works do go out of copyright, there are armies of fans, readers, and academics out there who take the time to scan, edit, and put them up online for our enjoyment, readable on tablets, ereaders, or plain old computer screens. Here are a few of the resources available online for free, public domain ebooks.

Exploring Ideas Through Fiction

A good book is one that makes us think--about ourselves, and about our world. Even in genre works, like sci fi, fantasy, and horror, the author still explores ideas about what it means to be human: love, hatred, trust, belief, war, disease--plus uncountable others. Even if an author doesn't intend to send a message in their work, the way that they present their characters and their setting will include certain assumptions and judgments about life.

A good book is one that makes us think--about ourselves, and about our world. Even in genre works, like sci fi, fantasy, and horror, the author still explores ideas about what it means to be human: love, hatred, trust, belief, war, disease--plus uncountable others. Even if an author doesn't intend to send a message in their work, the way that they present their characters and their setting will include certain assumptions and judgments about life.

There is no way to escape these themes, any more than writers can escape characters, plots, or words, so it is important for us to consider how we want to use them--and how they are used in authors we read. There are a number of ways to present and explore these themes in books, some more effective than others. So, in order from least to best, here are the different methods authors use to present ideas in their works:

I. Exploitation

Exploitative works present ideas in a way that thrills and titillates the audience, but which never asks difficult questions and does little or nothing to challenge societal prejudices. Such works use sex, violence, racism, religion, politics, and other hot-button issues to draw in their audience, exploiting the fact that, when we see such taboos being played out, it provokes strong emotional reactions from us.

The average Women in Prison Movie, for example, uses its setting to depict violence, nudity, lesbianism, and dominance, but it doesn't actually explore what these ideas mean. It doesn't try to define what 'justice' actually means, or look at the nature of personal freedom versus social safety. These are themes that are going to be present in any movie about incarceration, but in a low-quality exploitation film, such themes will never be explored. Of course, this doesn't mean that all movies labeled with the 'exploitation' genre must be this thoughtless--some use these techniques to get butts in seats, and can be remarkable subversive.

II. Realistic Presentation

These works present interesting themes to us in a realistic way, but never actually force us to confront them or think about them deeply. This was the criticism Roger Ebert laid against Fight Club: that the first half opens up a number of interesting questions, but the last half fails to sink its teeth into them, letting them drop away into the background. However, there are many exploitative authors who try to use this as a defense of their works--that they're only presenting the world 'as it really is'.

For example, recent authors of 'gritty' epic fantasy tend to present rape as a constant threat to women, often to the point that no female character in any of their books will fail to be threatened seriously with rape, at one point or another. They claim they are only representing 'the dark nature of war', but they never present a single male character being threatened with rape by his enemies, despite this being far from uncommon in the real world. As such, we can see that they are only presenting one side of rape, the side which our current culture finds titillating and exciting, meaning that they are writing pure exploitation, not realism.

Part of the problem with this strategy is that it acts as if the author and the work are somehow separate, allowing the author to deny responsibility for what they have written. All works of writing are artificial, because everything in a story is there only because the author chose to put it there deliberately, or because they unconsciously included it. Sitting back and saying 'no, my story is realistic, it represents the real world' is a cop-out. The book represents the author's views and mind, whether they intend it to or not, so to me it seems wiser to deliberately take advantage of this artificiality by being aware of it rather than pretending that it doesn't exist. Why choose to write a story about a prison if the theme of freedom doesn't interest you?

III. Promotion and Condemnation

This is the most simplistic way for an author to try to deal with themes in their work: to present the theme and then use various methods to try to convince the audience either that it is good, or that it is bad. Often, this means putting the idea into a certain character's mouth, such as having the hero give a long speech about the roles men and women should have in relationships. Since the hero is presented as good, and sympathetic, and competent, we are supposed to trust this speech and take the lesson to heart. Conversely, you can have the villain talk all about why Communism is the best, and since he happens to kill babies, we're supposed to conclude that Communism is evil. Sometimes, it's set up as a conversation, where the character the author wants to be right has all the proper answers, and the wrong character gets completely torn down.